In an age where women did not have the vote and had little political say, it was Elizabeth Heyrick’s attitude to money and finance that contributed to the influence women abolitionists had and changed the course of the campaigns from gradual to immediate abolition.

Elizabeth Heyrick grew up in an era when there was no compulsory or free education. There was no welfare or benefits available to anyone who could not work. Vagrants and debtors were imprisoned. In most families it made sense to send boys to school, but girls were restricted to Dame schools or the hire of a governess where they might learn household management, sewing, reading from the Bible and decorative arts with a view to making what would be considered a good marriage. Luckily for Elizabeth, her mother was a writer and valued reading. An unhappy accident for her brother Samuel, meant Elizabeth went to school in his place for some time as Samuel’s injuries put him out of action for six months. Although she would not have had the full range of lessons her brothers had, her education was wider than it was for many of her contemporaries. Her family were relatively comfortable and both parents modelled living within their means. Elizabeth was a skilled needlewoman and artist, good enough for her father to consider sending her to London to study. This move was blocked by her mother, perhaps worried her daughter would fall under the wrong influence.

On paper, her husband, John Heyrick – son of the Town Clerk and a practising solicitor – seemed a good match. However, their financial attitudes differed. John Heyrick had poor impulse control, including over money, and was happy for his family to bail him out. Widowed, Elizabeth was left with debts and sold furniture from their marital home to cover them, which embarrassed Elizabeth. Despite being a young widow – she was twenty-eight years old when John Heyrick died – her family did not pressure her to remarry. Her father gave her an allowance and she had no children, allowing her financial independence. Elizabeth Heyrick moved back into her parents’ home and opened a school in her former marital home at Bow Bridge. Although aware of her friend Susanna Watts' circumstances - Watts' father died when she was young, her mother was unable to work so it fell to Susanna to earn money through translations and her writing - there's no record of Elizabeth Heyrick loaning Watts money. Instead she offered Watts a teaching position at the school, giving her friend a regular source of income which still left Watts time to pursue other writing (and income) avenues and be an active member of the Leicester abolitionists.

How, then could someone becoming passionate about abolishing slavery, make her voice heard?

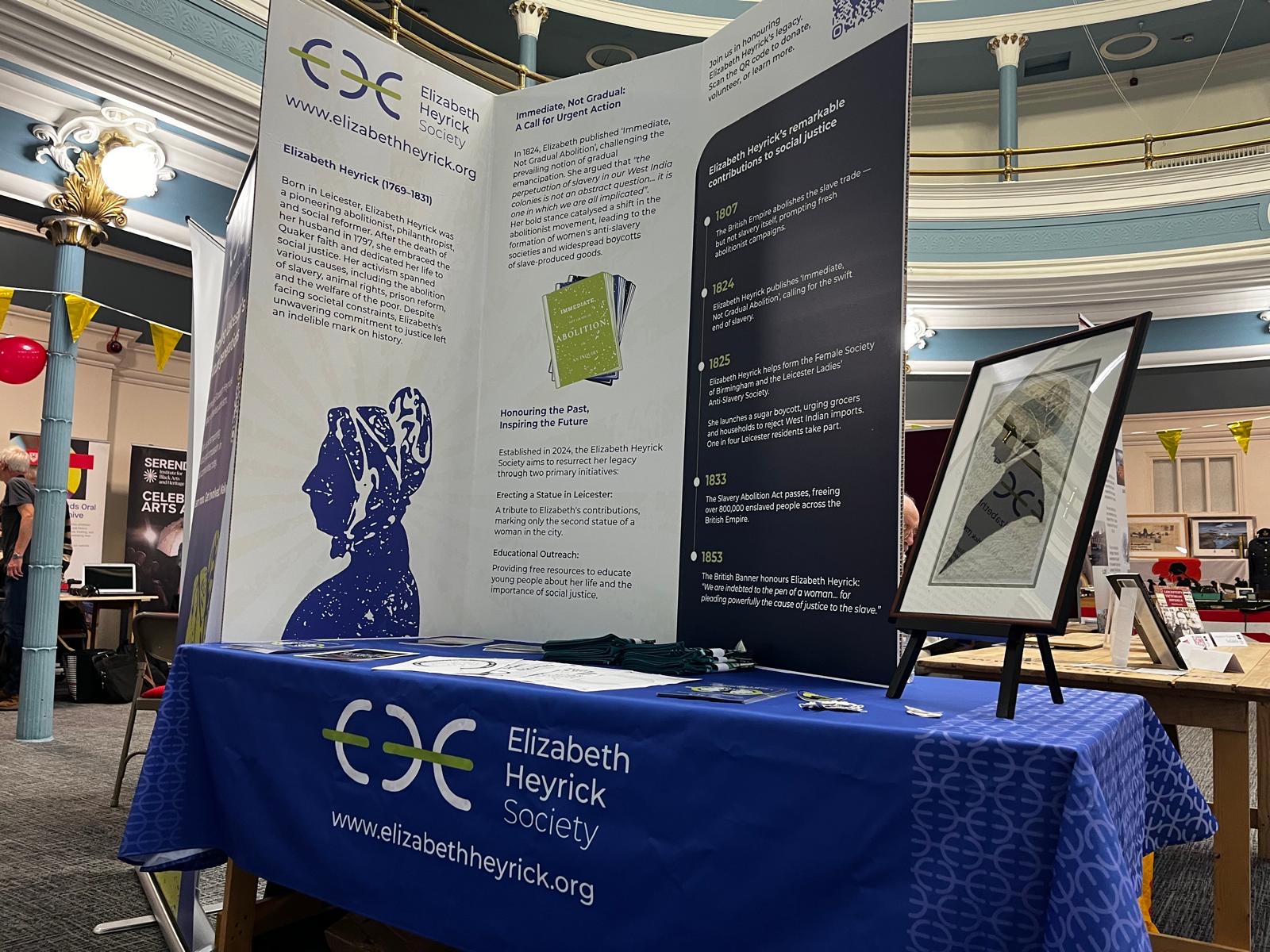

Elizabeth Heyrick understood that boycotting slave produced goods would mean a financial hit on the plantation owners. Although they may not have access to their own money, women still made purchasing decisions and did the household meal planning whether as the lady of the house or as cook. Persuading women to buy East India sugar instead of West Indian sugar would have the desired impact. A handful of households boycotting slave produced goods wouldn’t be enough. Households had to participate in significant numbers.

Women may not have been allowed to attend political meetings, but they could meet in sewing or book groups and establish female societies. Workbags, often simple drawstring bags with embroidered or printed embellishments, sized to take embroidery hoops, silks, linen and needles, were used to distribute anti-slavery tracts. The bags were decorated with embroidered symbols for freedom and hope or used images of mothers to appeal to women. Religion too played a part with its emphasis on fairness, justice and rewarding industry. The tracts were published anonymously. Women did write and publish songs, poems and novels, it wasn’t socially acceptable for their names to appear on the covers. It is remarkable that Elizabeth Heyrick’s “Gradual not Immediate Abolition” was published anonymously in Britian but her name appeared on the cover in the American print. Elizabeth Heyrick’s second abolition tract, “Appeal to the Hearts and Consciences of British Women” (1828) posited that women are more inclined to “sympathise with suffering” and also “to plead for the oppressed.”

Elizabeth Heyrick and friends also went door-to-door, directly encouraging the boycott. She also targeted grocers and confectioners. A cook couldn’t buy West Indian sugar if it wasn’t in the shop. Confectioners buying East, rather than West, Indian sugar would amplify the impact of the boycott. By 1825, approximately 25% of Leicester's population had stopped buying West Indian sugar.

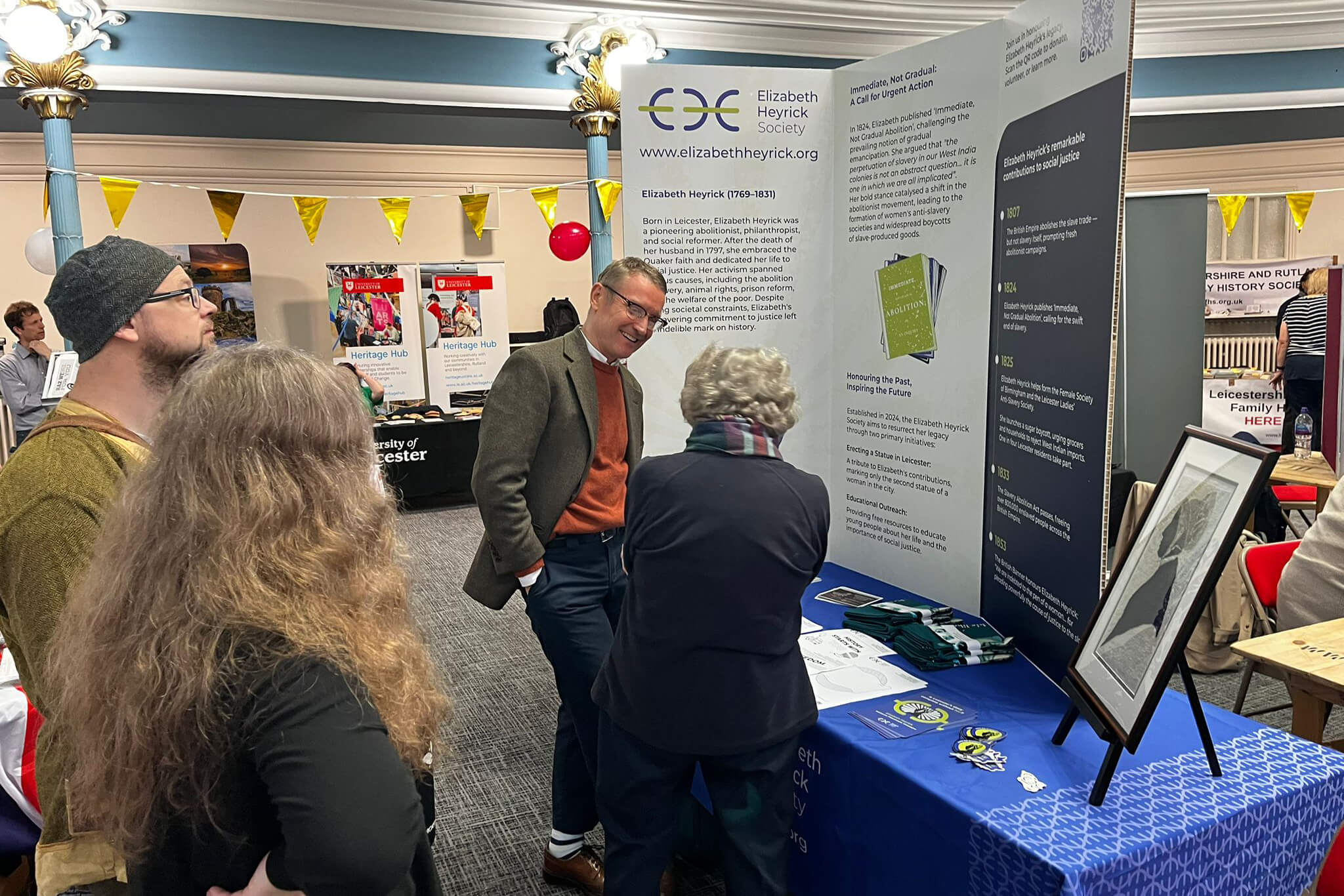

She horrified William Wilberforce who demanded those (mainly male-led) societies who supported gradual abolition to dismiss women’s contributions to the abolition campaigns. However, the weakness of these gradual abolition supporters was their reliance on financial contributions from the women’s abolition groups, the largest of which was The Female Society of Birmingham. Professor Clare Midgley has said,

“It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America”.

The Female Society of Birmingham’s Treasurer was Elizabeth Heyrick. Her proposal, in 1830, to stop sending financial contributions to the national anti-slavery society until, “they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title,” was accepted. In took a month for the Anti-Slavery Society to vote to drop the words “gradual abolition” and instead put their efforts towards an immediate abolition. Through her financial acumen, Elizabeth Heyrick succeeded in getting her voice heard.